Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy in the Black community

For Black people, the intersection of the COVID-19 pandemic and structural factors such as systemic racism, health care disparities, food insecurity, and disproportionate representation in the service (and what some may call the servant) economy has devolved into what laypeople say is a pandemic within a pandemic, but what scientists call a syndemic. Dr. Merril Singer, a medical anthropologist, first introduced the concept of a syndemic in the mid-1990s “to describe the co-occurrence and interactions between two or more diseases to disproportionately impact the health and well-being of marginalized communities.”

Building confidence in the process and the science is key for vaccines to be a contributor to addressing health inequities

COVID-19 Vaccine Education and Equity Project

Black Americans are contracting COVID-19, getting severely ill and dying from the disease at a much higher rate than other racial and ethnic groups. There is documented evidence that while it is a pandemic for other groups, Blacks are suffering in a syndemic. The gap in death rates between Black and Hispanic people and their white counterparts is highest in younger age groups. For example, the death rate for Black Americans aged 35-44 is over eight times that of whites in this same group. Black people aged 35-44 are about as likely to die of COVID-19 as white people who are 55-64.

Vaccine hesitancy is well-founded in the Black community because of a long history of racist medical experimentation that started with enslaved people and continued in the mid-1900’s, when Black men in Tuskegee, Alabama were deliberately not treated for syphilis so researchers could observe disease progression; and when Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells were harvested for research without her knowledge. While improvements have been made in recent decades to right those wrongs, many myths about Black people still prevail in the medical community. For example, a 2016 study showed that many white medical students still wrongly believed that African Americans have a higher tolerance for pain. Black people are underrepresented among clinical study participants – a consequence of historical mistrust in the first place. To this day, many of my well-educated friends in communities of color have expressed hesitancy about vaccines in general and now the COVID-19 vaccine in particular.

What I tell my friends about the Covid-19 vaccine

To do my part in combating vaccine hesitancy, I first acknowledge that hesitancy is understandable and justified in the first place. Then I make the case by sharing data points that I have collected over the past several months:

- Contrary to what many people have been misled to believe (by people seeking political gain) about Operation Warp Speed, the COVID vaccine is based on a scientific technology platform developed over more than a decade, predominated by scientists of color. Dr. Kizzmekia (Kizzy) Corbett of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), is the Black female scientist at the forefront of the COVID-19 vaccine development.

- Blacks have been well represented among the COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial participants. This represents a welcome change from many previous vaccine trials.

- Many medical and public health leaders, such as Dr. Uche Blackstock, have endorsed the safety and effectiveness of these vaccines. They are leading the charge on advising what the Biden-Harris administration needs to do to ensure Black Americans are not left behind in the vaccine rollout. They are teaming up with trusted Black celebrities, religious and community leaders to set the example by taking the vaccines themselves.

- Dr. Eugenia South, a Black doctor who didn’t trust the COVID-19 vaccine, described what changed her mind about vaccine hesitancy, and opines: “Let’s normalize hesitancy to take a new vaccine. Instead of judgment, we need to empower trusted messengers to answer community questions and dispel myths.”

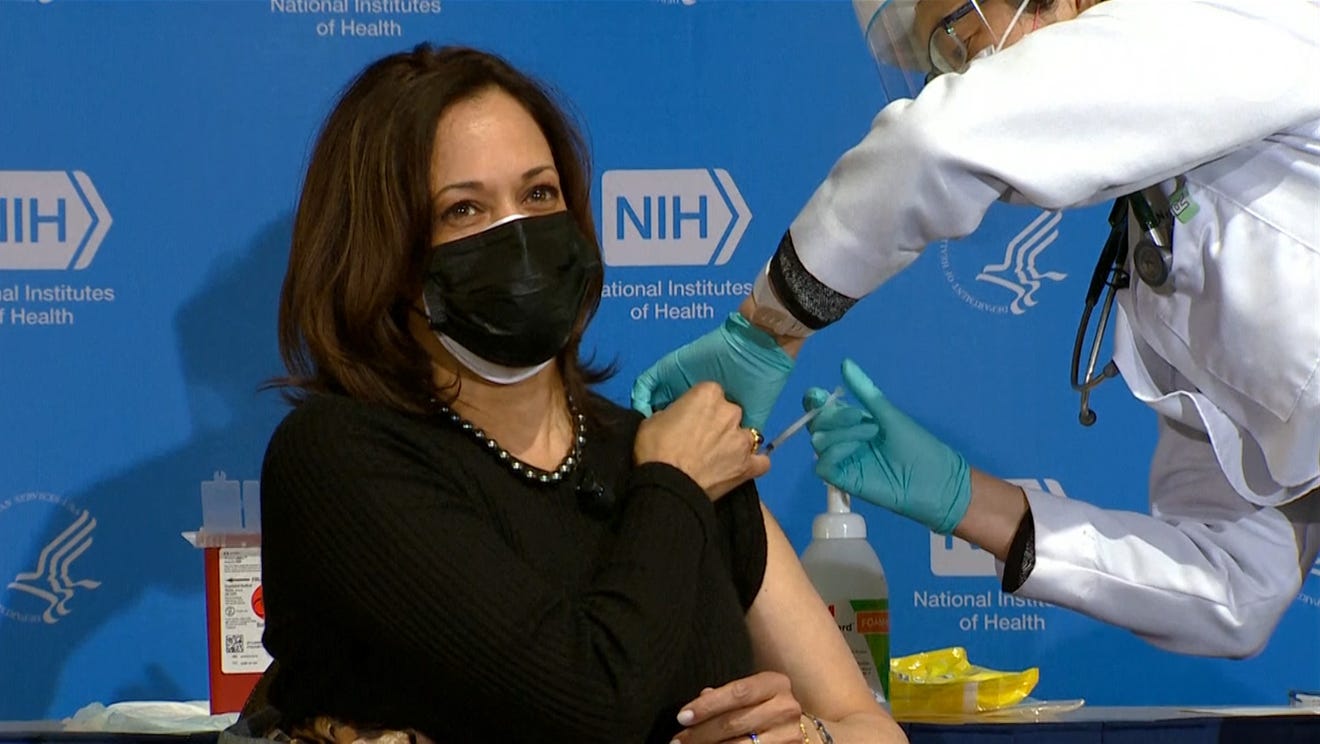

- What’s good for Madame Vice President (MVP) should be good for me.

- The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines developed thus far are roughly 95% effective in staving off severe illness, hospitalization and death. The side effects are also minimal. By comparison, the current influenza vaccine has been 45% effective overall against 2019-2020 seasonal influenza A and B viruses.

Why I am not throwin’ away my shot

Given that Black and Hispanic Americans have higher death rates in every age group than their white counterparts, it behooves communities of color to avoid contracting the virus in the first place. Now more easily transmitted variants such as B.1.1.7 (first detected in the UK), P.1 (first detected in Brazil) and B.1.351 (first detected in South Africa) are emerging and spreading across the US. While tactics such as wearing masks, watching our distance, and washing our hands regularly mitigate the risk of infection, vaccines are the primary weapon against the war on COVID-19; The fact that vaccine side-effects are relatively mild, whereas one of the side effects of COVID-19 is death, galvanizes me to get the vaccine as soon as one is available in my eligibility group.

vaccine side-effects are relatively mild, whereas one of the side effects of COVID-19 is death

Speaking of eligibility, it’s heartening to see that vaccine education and equity is a key factor in the Biden-Harris administration’s vaccine rollout in the US and around the world. Without hesitation, they are expected to implement the Defense Production Act (DPA) to build the syringes and other raw materials that are critical to vaccine production and distribution.

Winning the war against COVID-19 (and achieving herd immunity) begins with doling out vaccines first to those most at risk for suffering adverse effects. According to the COVID-19 Vaccine Equity and Equity Project, communicating transparent, scientifically accurate information about vaccines and vaccine technology is critical. Building confidence in the vaccine development process is also key to reducing hesitancy. I am committed to doing my part to encourage communities of color not to throw away their shot.